Happy honorary October 25th, O my peeps! Welcome to a not-at-all obscure Wheel of Time Re-read!

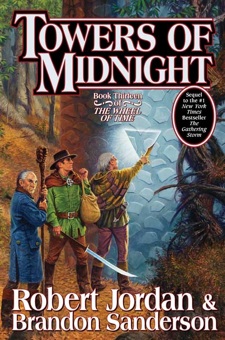

Today’s entry covers Part II of the Prologue of Towers of Midnight, in which I contemplate faith, brotherhood, and why sometimes both of those things kind of suck.

Previous re-read entries are here. The Wheel of Time Master Index is here, which has links to news, reviews, interviews, and all manner of information about the Wheel of Time in general, including the upcoming final volume, A Memory of Light.

This re-read post contains spoilers for all currently published Wheel of Time novels. If you haven’t read, read at your own risk.

And now, the post!

Prologue: Distinctions [Part II]

Prologue: Distinctions [Part II]

What Happens

Galad Damodred leads seven thousand weary and dispirited Children through a miserable swamp near the border of Ghealdan and Altara, and tries to look unaffected by the terrible conditions for his men’s sake. Dain Bornhald joins him and suggests that perhaps they should turn back, but Galad tells him they must continue forward.

“I have thought about this much, Child Bornhald. This sky, the wasting of the land, the way the dead walk There is no longer time to find allies and fight against the Seanchan. We must march to the Last Battle.”

Bornhald is uneasy about the swamp, which the map had not shown, and Galad thinks that all their maps have become unreliable. He tells Bornhald to gather the Children up so that he may speak to them. He tells the assembled men that these are “the darkest days of men,” but that the light always shines the brightest in the dark, and they are that light. He says their afflictions are their strength, and that he is proud to be in this swamp.

“Proud to live in these days, proud to be part of what is to come. All the lives that came before us in this Age looked forward to our day, the day when men will be tested. Let others bemoan their fate. Let others cry and wail. We will not, for we will face this test with heads held high. And we will let it prove us strong!”

The men’s flagging morale improves in the wake of Galad’s speech. Galad meets with Byar, who fervently praises Galad’s speech, and opines that their numbers will grow, perhaps enough to cast down the witches. Galad tells him that they will need the Aes Sedai to face the Shadow, and Byar reluctantly agrees. Galad then goes to the van, where his scout leader, Child Bartlett, shows him that their path ahead is blocked by a shallow river which had not been there before, cutting through a dead forest and choked with corpses floating downstream from somewhere. Galad insists on going first to ford it; the army crosses the fouled river without incident, but is exhausted by the effort. Galad tells Trom he plans to take them to Andor, to where he has personal lands; he prays that Elayne has gained the throne by now, and not fallen prey to either the Aes Sedai or al’Thor. Trom confesses he was worried Galad would refuse leadership, but Galad replies he had no choice in the matter; it would have been wrong to abandon the Children.

“The Last Battle comes and the Children of the Light will fight. Even if we have to make alliances with the Dragon Reborn himself, we will fight.”

For some time, Galad hadn’t been certain about al’Thor. Certainly the Dragon Reborn would have to fight at the Last Battle. But was that man al’Thor, or was he a puppet of the Tower, and not the true Dragon Reborn? That sky was too dark, the land too broken. Al’Thor must be the Dragon Reborn. That didn’t mean, of course, that he wasn’t also a puppet of the Aes Sedai.

Bartlett reports that the land dries up to the north, and Galad has the company push ahead eagerly, but when he clears the trees, a force of some ten thousand Children and Amadicians provided by the Seanchan crest the rise opposite, led by Asunawa, and Galad realizes Bartlett has led him into a trap. Byar goes to kill Bartlett, but Galad stops him. He orders Trom to have the men form up in ranks, and takes Byar and Bornhald to parley with Asunawa, who brings far more men with him, including five Lords Captain. Asunawa orders Galad to have his men stand down or his will open fire; Galad asks if he will abandon the rules of engagement and honor. Asunawa snaps back that Darkfriends deserve no honor. Galad asks if he really means to accuse all seven thousand Children behind him of being Darkfriends; Asunawa hesitates, and allows that perhaps they are merely misguided, being led by a Darkfriend. Galad refutes the accusation, and orders him to stand down; Asunawa laughs and counters that it is Galad who must surrender.

“Golever,” Galad said, looking at the Lord Captain at Asunawa’s left. Golever was a lanky, bearded man, as hard as they came—but he was also fair. “Tell me, do the Children of the Light surrender?”

Golever shook his head. “We do not. The Light will prove us victorious.”

“And if we face superior odds?” Galad asked.

“We fight on.”

“If we are tired and sore?”

“The Light will protect us,” Golever said. “And if it is our time to die, then so be it. Let us take as many enemies with us as we may.”

Galad turned back to Asunawa. “You see that I am in a predicament. To fight is to let you name us Darkfriends, but to surrender is to deny our oaths. By my honor as the Lord Captain Commander, I can accept neither option.”

Asunawa says Galad is not the Lord Captain Commander, and that he drew on “the Powers of the Shadow” to win his duel with Valda. Galad turns to another Captain with Asunawa, Harnesh, and asks if the Shadow is stronger than the Light. Harnesh replies, of course not.

“If the Lord Captain Commander’s cause had been honorable, would he have fallen to me in a battle under the Light? If I were a Darkfriend, could I have slain the Lord Captain Commander himself?”

Harnesh doesn’t answer, but Asunawa counters that sometimes good men die. Galad says he had every right to challenge Valda for what he did, and Asunawa spits that Darkfriends have no rights. Galad asks what happens if Child fights Child, and suggests that they can reunite. Asunawa rejects this, but hesitates, knowing that even though he would win, the cost of a full-scale battle would be devastating for both sides. Galad tells him he will submit to him, as long as he swears that Asunawa will not harm, question or condemn any of his men, including Byar and Bornhald.

“The Last Battle comes, Asunawa. We haven’t time for squabbling. The Dragon Reborn walks the land.”

“Heresy!” Asunawa said.

“Yes,” Galad said. “And truth as well.”

Bornhald softly begs Galad not to do this, but Galad replies that every Child who dies at another Child’s hand is a blow for the Shadow, and they are “the only true foundation that this world has left”. If his life will buy unity, then so be it. Asunawa is aggravated, but accepts. Galad orders Bornhald to make sure the men stand down and do not try to rescue him. Then the Questioners haul Galad out of his saddle and throw him down roughly, using knives to strip him of his armor and uniform.

“You will not wear the uniform of a Child of the Light, Darkfriend,” a Questioner said in his ear.

“I am not a Darkfriend,” Galad said, face pressed to the grassy earth. “I will never speak that lie. I walk in the Light.”

That earned him a kick to the side, then another, and another. He curled up, grunting. But the blows continued to fall.

Finally, the darkness took him.

The creature that had been Padan Fain/Mordeth walks north into the Blight, away from the corpse of the Worm he had just killed, a familiar mist trailing him. He is cutting himself on the ruby dagger, scattering his blood on the ground, and enjoying the black storm in the sky even though he hated the one who had made it.

Al’Thor would die. By his hand. And perhaps after that, the Dark One. Wonderful

He thinks he is mad, and that it had set him free. He comes to where a group of Trollocs and a Myrddraal were hiding from the Worm. The Trollocs attack, but the Fade holds back, sensing something is wrong. Fain/Mordeth smiles, and the mist strikes.

The Trollocs screamed, dropping, spasming. Their hair fell out in patches, and their skin began to boil. Blisters and cysts. When those popped, they left craterlike pocks in the Shadowspawn skin, like bubbles on the surface of metal that cooled too quickly.

The creature that had been Padan Fain opened his mouth in glee, closing his eyes to the tumultuous black sky and raising his face, lips parted, enjoying his feast.

He walks on, and the corrupted Trollocs get up and follow him sluggishly, though he knows that when he wants them to they will fight with berserk fury. The Fade does not rise, for his touch is now instant death to its kind. He thinks it is sad that his hunt for al’Thor is over, but that there is no point in continuing a hunt when you know exactly where your prey is going to be.

You merely showed up to meet it.

Like an old friend. A dear, beloved old friend that you were going to stab through the eye, open up at the gut and consume by handfuls while drinking his blood. That was the proper way to treat friends.

It was an honor.

On the border of the Blight in Kandori, Malenarin Rai, the commander of Heeth Tower, goes through supply reports. He finds a reminder from his steward that his son Keemlin’s fourteenth name day is three days hence, and smiles in anticipation of giving his son his first sword and declaring him a man. He goes on his daily rounds, reflecting proudly on the superb defenses of the tower, and meets Jargen, a sergeant of the watch. Jergen reports that there was a single flash from Rena Tower to the Northwest, but no correction for it. Malenarin goes up to the top of the tower with Jargen and waits, but no further message arrives. Malenarin orders a message flashed to Rena inquiring, and another to Farmay Tower to check in, even though Jargen indicates they’ve done that already.

Wind blew across the tower top, creaking the steel of the mirror apparatus as his men sent another series of flashes. That wind was humid. Far too hot. Malenarin glanced upward, toward where that same black storm boiled and rolled. It seemed to have settled down.

That struck him as very discomforting.

He orders a message sent to the inland towers as well, advising them to be ready. He asks who is next on the messenger roster, and Jargen tells him it is his son Keemlin. He tells Jargen that they must send several messengers south, in case the towers are not receiving. He writes the message (“Rena and Farmay not responding to flash messages. Possibly overrun or severely hampered. Be advised. Heeth will stand“). He allows himself to feel relieved that Keemlin will be riding to safety, in case the worst has happened. He watches the storm again, noting the strange shapes of the clouds, and suddenly realizes the leading edge of the cloud is advancing. He orders the tower garrison to prepare for a siege, and turns to find Keemlin behind him. He demands to know why Keemlin is still there, and Keemlin tells him he sent Tian in his place. Keemlin adds that Tian’s mother has already lost four sons to the Blight, and he figured if any of them should have a shot at getting out, it should be Tian. Malenarin gazes at his son, and then sends a soldier to get the sword in the trunk in his office. Keemlin says his nameday isn’t for three days, but Malenarin tells him that the weapon is offered to a boy when he becomes a man, and he sees a man before him. All the soldiers stop to watch.

As Borderlanders, each and every one of them would have been given his sword on his fourteenth nameday. Each one had felt the catch in the chest, the wonderful feeling of coming of age. It had happened to each of them, but that did not make this occasion any less special.

Keemlin went down on one knee.

“Why do you draw your sword?” Malenarin asked, voice loud so that every man atop the tower would hear.

“In defense of my honor, my family, or my homeland,” Keemlin replied.

“How long do you fight?”

“Until my last breath joins the northern winds.”

“When do you stop watching?”

“Never,” Keemlin whispered.

“Speak it louder!”

“Never!“

“Once this sword is drawn, you become a warrior, always with it near you in preparation to fight the Shadow. Will you draw this blade and join us, as a man?”

Keemlin looked up, then took the hilt in a firm grip and pulled the weapon free.

“Rise as a man, my son!” Malenarin declared.

Keemlin stood, holding the weapon aloft, the bright blade reflecting the diffuse sunlight. The men atop the tower cheered.

Malenarin blinks away tears, and knows the men cheer not just for his son, but in defiance of the Shadow. Then one of the archers spots Draghkar in the clouds, and the unnatural clouds are close enough to reveal the massive horde of Trollocs advancing beneath them. Jargen suggests Keemlin should be below, but Malenarin replies that Keemlin is a man now, and stays. Malenarin watches the Trollocs approach, and knows that the tower will not be able to withstand them for long.

But every man atop that tower knew his duty. They’d kill Shadowspawn as long as they could, hoping to buy enough time for the messages to do some good.

Malenarin was a man of the Borderlands, same as his father, same as his son beside him. They knew their task. You held until you were relieved.

That’s all there was to it.

Commentary

I ain’t gonna lie: the end of the Prologue got me choked up just now.

The nameday ceremony scene might not quite have been on the level of St. Crispin’s Day (which I acknowledge is a wholly unfair comparison to make, because hello, Shakespeare; also, sorry, but Richard Burton’s version of that speech so beats Olivier’s), but the emotions it evokes are much the same, for much the same reasons, and I seem to recall that following ToM’s release, quite a few people picked this scene out as being one of the most moving parts of the novel for some, of the entire series. I would not go quite so far as the latter group, but I wholeheartedly agree with the former.

The thing is, though, that I don’t think I responded to this scene nearly as strongly when I first read it, over a year and a half ago now, as I did when I re-read it just now. The reasons why are interesting (well, I think they are, anyway), and have to do with factors completely separate from the Wheel of Time or anything associated with it.

For reasons which are many, I’ve been on something of a military fiction kick lately. Mind you, I’m not talking about the overblown, improbable, Michael Bay handjob bang-bang-shoot-’em-up co-opting which is Hollywood and pulp fiction’s usual approach to the military and which, in my opinion, often accomplishes the remarkably paradoxical feat of diminishing the armed forces by attributing to them unrealistically superhuman capabilities and purity of purpose when it’s not turning around and demonizing them in the next breath, of course. I’m not talking about that; I’m talking about the stuff out there that makes a genuine attempt to portray the military, and particularly the people who comprise that body, in a way that is as true to life as can reasonably be expected, with all their believable amounts of heroism and honor and all their just as believable lack thereof.

(In that vein, I must give my obligatory plug for the tragically undersold and overlooked HBO miniseries Generation Kill, which is one of the few mainstream portrayals of the Iraq War yet produced that remotely does it justice, in my opinion, and additionally happens to be one of the best written, directed, and acted pieces of television I’ve ever seen. It’s not easy to watch, but it is so, so worth it.)

Anyway, my point in bringing this up is that no even remotely honest portrayal of any military body can fail to address the subject of the St. Crispin’s Day speech, which can be summed up in its most famous passage:

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he today that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother.

So I have by default been rather immersed lately in the various fictional contemplations of this bond between soldiers, between those who fight and bleed and sometimes die together for a common cause, which has been pondered and expounded upon and romanticized (and sometimes over-romanticized) throughout history, and again right here in the Prologue for ToM. And for me personally, one of the things I find so fascinating and simultaneously so aggravating about it is how thoroughly it seems to exclude me. By virtue of my status as a civilian, of course, but even more completely in that I am female.

And “aggravating” isn’t even really the correct word, I think; it’s more almost a a wistful feeling, that I am denied even the possibility of entrance to this so-honored group, by the very language it is couched in. It’s a band of brothers; there are no girls allowed. The scene where Keemlin receives his sword is, in fact, very specific in how it emphasizes that this is a ceremony for Borderlander men; it is, literally, how they become men in their culture, and (by all appearances) how they define themselves and their relationship to each other by that common bond, and there is nothing of women in it at all. And even today’s (U.S.) military still draws that distinction, by dictating that women who serve are not allowed in combat which essentially denies them the most fundamentally honored aspect of serving in the military in the first place.

I’m not interested, at the moment, in debating whether or not that is a good thing; my point is, it’s a thing. It exists, this exclusion, is what I’m saying, and I am therefore unable to avoid acknowledging it.

So I feel the power of that brotherhood, and am moved by it, at the same time that I am saddened by the fact that I am not allowed to even vicariously imagine myself a part of it. And far more, I think, now that I have been made so much more aware of this dichotomy than I was previously. And I honestly can’t be sure which aspect of that affected me more, reading this scene.

Because I’m not a warrior, and I don’t want to be a warrior but it would have been nice if I’d been allowed to even have the option of wanting it.

Anyway.

Fain: is icky. And cray-cray. And can apparently create zombie Trollocs with his travel-size Mashadar kit, because Trollocs totally needed to be grosser than they already were. And is on his way to Mount Doom Shayol Ghul to ambush Rand. Huzzah.

Galad: I swear, both of Elayne’s brothers have an almost supernatural ability to make me root for them and yet simultaneously make me want to smack them upside the head. Hard.

Galad less so than Gawyn, of course, because Gawyn is the undisputed champion in the needing-head-smackings arena, but some of what passes for logic in Galad’s brain is positively jaw-dropping. Even as I was cheering him on for out-theologizing Asunawa, I was at the exact same time yelling OH COME ON at some of his “reasoning.”

But this, admittedly, is precisely where I personally have a fundamental disconnect with the religious mindset. I have never understood the belief that God (or the Light, or whatever) protects those who are faithful and pray and follow the rules of that God, in the face of the absolutely overwhelming evidence that ill fortune and disaster makes no distinction whatsoever between the virtuous believer and the godless heathen when it strikes. Hurricane Katrina (just for example) killed a little over 1,800 people when it blew ashore, and I guaran-fucking-tee you there were just as many God-fearing church-going folk among that number as there were sinners and atheists. In fact, statistically, there were probably even more of the first group than the latter two (which are, contrary to what some believe, actually separate categories).

So basing an argument over who was “supposed” to win a sword duel on the participants’ spiritual allegiances (as opposed to, say, which one was a better swordsman) is simply ludicrous to me, just as much as the supposition that believing in God will make you more likely to survive a Category 5 hurricane than someone who doesn’t. Sorry, but it won’t. (You can argue about whether it will affect what happens to you after you die, but that’s a whole other can of worms.)

And to anticipate the obvious counterargument, there is no more evidence that the WOT version of God chooses to intervene in the randomness of the Pattern than the Christian version does, at least not so directly and minutely as to influence the outcome of one non-Messiah-involved sword duel. In fact, in the entire series, the only “direct” action we’ve seen the Creator take was when he showed up in TEOTW to tell Rand that he would take no part in the action!

That said, I certainly concede that for the particular audience Galad was playing to, his choice of argument was the perfect one to make, and I was totally rooting for him to win with it (even if he, well, didn’t, at least not at this point). It just kind of also made me want to beat my head against my desk at the same time.

Sigh. Well, he gets more awesome later, so I’ll just look forward to that, shall I?

And, yeah. So now that I have totally not said anything controversial at all in this post, we out! Have fun, play nice in commentage, and say goodnight, Gracie!

Thanks for the reread this week!

I loved Galad’s argument and reasoning. It’s all about context for me. While I don’t agree with the beliefs and assumptions of the Children of the Light, I always try to appreciate a well thought out and logical argument. In that, Galad succeeds beyond a doubt. Though his logic is based on what I consider false assumptions, in the context that he was arguing with those that [should] believe in those assumptions, he made some great arguments in pointing out the blatant disregard for Children policies showcased by Asuwana. For once, the stick up Galad’s ass actually worked for something cool (also true of him killing Valda), not just judgement and condescension, so that’s a victory in my book!

Great post Leigh. I was not aware that the end of the prologue had such an overwhelming response from the fans but I’m certainly among those that thing it’s one of the more moving moments in the entire series. I have no personal life experience to base it off of other than admiration for those that I know that have such unflinching dedication to do their duty and protect others.

This was the first time since starting TGS that after reading something I thought was particularly amazing I didn’t wonder or care who was responsible for the writing because I thought it was transcendentally awesome.

I was almost equal parts happy and frustrated by the start of the Galad plotline in this book. I felt like his first 3-4 POVs were an accelerated version of the Egwene/White Tower plotline. Galad sacrifices himself and endures hardships for his people and they rally to him and unite under him. Mostly, the feeling I had on first reading and still was that some of this should have been thrown into TGS. The gap from the prologue of Knife of Dreams to now just always felt very jarring to me.

For what it’s worth, Leigh, fathers feel the same “not invited to the party” feeling when they have children. The mother is in a special club of 1, and men are not really invited. Even when women go out of their way to include the father, there is a sort of barrier there that cannot be crossed. The thing about it is, women and men are…different.

That means something, and it has practical implications.

Great reread again.

What I find interesting ie. Christian mindset (I’d like to think I’m one of those God-fearing Church-going people myself :) ) is that nowhere in the Bible does it mention anything about direct intervention by god. In fact, both Testaments mention this idea:

Ecclesiastes – Time and unforeseen circumstances befall them all.

Luke 13 – The Tower of Shiloam, Jesus clearly states that those who died did not die because they were more sinners but because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Still, as in our world in Randland, there is nothing to indicate that just because someone who claims to speak for God says something does not at all mean that they actually represent his views.

Just by two cents. Thanks again for all your hard work on this reread. I’m doing my own reread at the moment (Up to Shadow Rising this month) and after every chapter I’ve been checking in with your commentary here at the reread.

Mmm, exclusion… Men and women are different, but refusing womens’ service or putting them on pedestals, which all the borderlanders are guilty of, is ridiculous.

I’m reminded of Éowyn from LOTR:TTT – no Man can slay the witch-king, bitches.

Are you saying that women do not have some sort of sisterhood that allows them a bond that men cannot share in? I would think that motherhood would qualify.

And it is written that the rain falls on the just and unjust alike.

Dragon

edit

BenPatient@@.-@: Vive la différence!

@@.-@ Beat me to it

As Leigh mentioned in her read of Ice and Fire early on, a fantasy author has two choices concerning women in midevil (sp?) type worlds. Either the author can create a fantasy world where men and women are treated equally or they can rub the reader’s nose in the inequality.

Personally I find it distracting to the story when there are women pushing spears with the men and not getting bowled over by the generally greater mass and muscle. Jordan did well in avoiding either trope by creating from the beginning a situation where women would logically have more power given that they were the only “mages” left.

As for women in combat today that doesn’t depend as much on muscle power, I’m all for it as long as the woman in question can pass the same standards the men have for what muscle power is required.

Back to the prologue; Galad in this book gets to be the exact same person he’s been all series but instead of being a pain is the perfect person for the situations he is in. That is some good writing. And as for the borderlanders, wow. I have a feeling like the Aiel, they’re going to have a blaze of glory only to see their wonderful culture decay in the aftermath with no more threat to keep them together. But for the moment, ALL of them are just constantly keeping up those MOA.

There’s no denying that Fain has become scary/creepy, but I wish there had been a bit more foreshadowing or indications of his oncoming powers.

The last time we saw Fain was all the way back in Winter’s Heart where he had his usual bag of tricks (illusions and a very dangerous dagger.) There was no hint then that he could do any of the things we see in this snippet.

What’s a bit more worrisome is that the text seems to imply that we won’t see him again until the showdown at Shayol Ghul. So there’s little chance we’ll learn more about his powers (and any limitations.)

For those who think of Fain as WoT’s “Gollum” – consider how Gollum was “on screen” a lot as the series approached it’s climax. No red herring, no deus ex machine, he was integral.

Fain, OTOH, is beginning to feel more like a distraction or footnote. If he is slated to play an important part in the final scenes, we may yet regret that we didn’t see more “character development” (maybe “character debasement”?)

Hello, I changed my handle. Was “Would be Brown Ajah”, but since 1/3 to 1/2 of the people on the comments could say the same thing, I went with something else. Yes, I like Ny. But the picture is the braid I always give Birgitte in my head.

Post Comments:

Galad – once again we have a charter saying basically “we are the only hope the world has left.”

He thinks the CoL are the “only true foundation left in the world.”

Eqwene thinks the AS are the only thing standing in the way of the Last Battle.

Rand, the World’s Savior, is now running around bringing hope. Lan is about to lead a gathering of people to the Gap. Lots and Lots of people are doing great things in order to fight the “Last Battle.”

Look at the Borderlanders at this random watch tower! What a great moment.

Could our speaking part charters please stop being so selfish and arrogant as to be believe their group is the only one doing anything?

Edit: Leigh, we don’t know what the naming day ceremony is for the Borderland women. It could be just a moving in a different way.

Different = Okay be me. Can we drop the gender being different does not = Equality discussion?

Fain / Mordeth – anyone else thrown by all “the creature once know as…” Since this is from HIS POV, would he really think like that? It seems an odd way to talk about yourself, even if you are crazy…

I think Galad may have been making that argument to refute the claim that the only way Galad won was to draw on the power of the Shadow – that the fight had some kind of supernatural element to it. I also find the concept of ‘trial by combat’ ridiculous though (ie, the ‘trial’ at the Eyrie in Game of Thrones).

I am a pretty religious person, as are many of my friends, and I don’t know many that seriously believes that being religious protects you from harm. I know the mindset exists, I just don’t know anybody who holds it. For any thoughtful, discerning religious person, the point of being religious is because you think it’s true, that God deserves honor, for more eternal reasons than this life here on earth (Note: I am speaking from a Christian standpoint, so this may not apply equally to all other religions).

It doesn’t mean that there might not be blessings or miracles, or that the general principles of the religion aren’t generally going to lead to a more ordered and rewarding life (ie, if you are generally kind to your neighbor, honest, hard working, temperant you will probably have a better life than otherwise, although of course that doesn’t always happen – sometimes bad people prosper and good people suffer through no fault of their own, something the Old Testament Psalmist decries often) – but that’s not the point. There’s more to it than that. Also, many times those ‘blessings’ aren’t what we would think of as blessings in the worldly sense (ie, riches, material things, etc). In fact, many times in Scripture it talks abou there being trials, thorns, persecutions, and the fact that evil is still a very real thing in this world that we have to deal with, and people have the free will to do evil acts. Being religious just helps make dealing with that easier, it doesn’t mean your life is going to always be awesome. I have seen people who expect that end up with a very unpleasant shock and usually end up disillusioned.

I do know there are people to tell their kids stuff like that, though (ie, ‘say your prayers, be a good girl, and it will be okay’ and it actually irritates me. Sometimes things aren’t okay, but it’s not necessarily due to a lack of piety.

Anyway, back to Wheel of Time :). One thing that struck me in this re-read was that Galad’s response was basically what should have happened in the White Tower – he attempts to reconcile for the sake of unity in the face of a more pressing problem. Not that I think Egwene et al were wrong to overthrow Elaida, especially as it became apparent that she would lead them all to destruction (especially as she is the one that started her own coup), but I think many of the people in the Tower were wrong for encouraging/prolonging the schism (something that they touch in in the conclusion of TGS).

This may be dense of me, but what is the signficance of October 25? Aside from it being my wedding anniversary ;)

What, no mention of the Dragon orbiting over our heads right now?

I tend to agree with Leigh’s impression of Galad’s theology, or whatever you want to call it. He arrives at the “right” conclusion, but wow what a logical trainwreck he rides to get there. Leigh, I also agree about your assessment of the efficacy of relying on God to take a direct hand to protect you in a catastrophe – ain’t going to happen. Though personally I would point at, perhaps, a more direct parallel to the sword duel – all those athletes praying to God to help them overcome their opponents (who are also praying to God for the same thing…). Sorry, but somehow I don’t think God cares whether believer #1 or believer #2 or atheist #9 wins the football game (unless believer #1 is Didier Drogba, of course – anyone catch the UEFA Championship final?).

Galad – I do enjoy the Questioner smackdown er beheading in the next chapter or so.

Fain – What’s the guys name in the TV movie “The Stand” who came in on the nuclear golf cart? Anyway he would make a great Fain!

Heeth Tower – Great and touching scene.

When I first read this prologue, it immediately evoked the St. Crispin’s Day soliloquy, though neither as delivered by Olivier nor Burton, but Branagh. And thank you Leigh for ensuring the connection. More than fitting.

OTOH, take it easy on Galad. If he had genuine doctrinal righteousness on his side, he wouldn’t have given Berelain a second glance, and we couldn’t have had that, right?

To be clear, while some make a claim to divine protection by virtue of their faith, often by misusing Romans 8:28 (“And we know that all things work together for good to them that love God, to them who are the called according to his purpose.”), the truth is that God involves Himself for the purpose of His will and His plan, and not our own. The verse quoted above does not say that all things are good for the faithful, but that all things work together for good. Today’s tragedy, or discomfort, or disaster has designs embedded which we, who are among the warp and the woof, cannot see from within the great tapestry, but on that day, we will see and know.

Using the currently popular example, Tim Tebow does not pray for God to help his team win, rather that he might, through God’s grace, perform well and not dishonor his Creator. Any petitions brought by a believer before the Throne, should conclude with the caveat, ‘if it be your will’. We cannot know why and how He moves, but we can trust that His purpose is just.

LisaMarie @12

St. Crispin’s Day. Also, long time since I’ve noticed a comment from you. I remember that my first entry on this reread followed a post by you.

@@.-@ – YES, totally agree. I also think that human beings (male and female) have many other ways (aside from combat) to feel and gain the same kind of honor. When anyone faces up to something difficult and doesn’t back down, I see that as honorable in the same sense. Be it single parenthood, beating addiction, surviving a sickness, standing up for what’s right, etc. There is definitely a sense of “brotherhood” in each of those situations as well.

Keemlin’s 14th naming day scene is awesome! The only scenes I ever cry during are the scenes about honor or self sacrifice for a just cause (this scene was no exception).

Galad is mostly a pain through all of WOT but I agree that I am totally rooting for him at this point and situation. Maybe that’s because I seriously hate Asunawa’s guts though? Meh.

I just want Fain to die. :/

Seamus1602 @@@@@ 2

“For once, the stick up Galad’s ass actually worked for something cool

(also true of him killing Valda), not just judgement and condescension,

so that’s a victory in my book!”

ROTFL!

Yes, you nailed it! While his half-brother’s antics in the realm of idiocy tend make him look better by comparison, Galad has always bothered me by his totally moral absolutist outlook and UN-impeachable (though very superficial) confidence in his ability to determine what the “right thing” is. As someone who is religious, and believes in certain moral truths, I have always found him to be somewhat of a caricature, rather than a true character. I mean no adult, barring a serious mental disability, is that unquestioning and certain at all times of the philosophical rightness of a course of action in every situation as this. He is so superficial, it is like using Ned Flanders as a model for a serious study of modern Christianity. I know he gets a wake up call later in the book, and that is at least some character development, and his father was kind of a manipulative slime ball (not to mention his mother running out on him), but the kid kind of strikes me as more supremely naïve than anything.

As for the Whitecloaks in general, they have always struck me as being similar to many very like-minded medieval organizations that exited in real life, some people/organizations hold views like that, it doesn’t mean all religious practice needs to be painted with that brush. And Galad’s logic was impeccable, given the context of the situation.

ShiningArmor @@@@@ 3

Yes, I too felt that Galad’s first few points of view here were a condensed version of Egwene’s story arc in tGS. The parallels are quite close.

Leigh,

I understand where you are coming from and agree with you. That said, take it from a guy who’s been in for twenty years. Being a part of the ‘Brotherhood’ isn’t all that it’s cracked up to be. It loses most of its luster once you see a few friends die. It truly brings the rest of you closer, but the price is way too high. Also, just to let you know, women are finding themselves in harms way more and more. They can be just as brave or cowardly as anyone else, and they can die just as quickly/horribly as anyone else. IED’s & bullets don’t care what type of plumbing you have, and war does not care who gets chewed up and spit out. It’s the very last word in equality.

If you haven’t already; give “The Killer Angels” a try. Truly one of the best books on this subject (Profession of Arms not gender equality) ever written.

The reasoning used to be that women (aside from having to be making sammiches and having kids only) weren’t strong enough, in general, to weild swords, bows, spears, and such. Today this is changing, slowly but surely- a very few small countries can’t afford to exclude half of their healthy bodies, and in the US women are seeping in. Females have been Naval Aviators flying combat aircraft for years, have been stationed aboard (and commanded) USN combat ships, and are beginning to be placed on (in?) USN missile submarines.

Shooting a rifle or sitting at a console is apparently someting that both sexes can accomplish! Yay!

Sexytimes are an entirely different issue, though; even from

real worldcivilian situations.Leigh, I truly appreciate everything you’ve done with the re-read; it’s been an absolute blast reading through it, and it’s been extremely helpful in letting me tell new readers that they can really just skip books 7-11 because there are already fantastic chapter summaries online for people to read through (otherwise, people invariably get to Path of Daggers and just give up on the series). You’ve truly done a wonderful job.

That said, I have to say my mind continues to boggle at just how it’s possible for you to insert gender politics into literally everything. 90% of the things I read online, you can’t tell if they were written by a man or a woman, and the rest of the time you can only tell because they mention some gender-specific personal life event in passing. I’ve literally never run in to somebody whose worldview and interpretation of outside events seems to be shaped by their gender, and I have to admit that it’s extremely distracting. I’m not sure if it’s a new thing for you (I may be wrong, but I seem to remember you having been on rasfwrj back in the day, and I don’t recall this kind of perspective), but it really does distract from the otherwise fascinating commentary.

Leigh,

Women today do serve in combat. Women are allowed to be in field artillery and transportation units which does expose some to combat. Granted, most aren’t exposed to it but they are given that opportunity. Also women are going to start being able to go to Ranger school now (a type of Special Forces) which will mean they are in infantry/armor type jobs.

Oh yay! One of Leigh’s patented over-the-top rants about gender issues. Plus, religious zealots!

/headdesk

/headdesk

/headdesk

Giving the son a sword was a touching moment, and was very well written. Not my personal favorite, but right up there (mine was Nyneave recruiting an army for Lan).

Braid_Tug@11 Could our speaking part charters please stop being so selfish and arrogant as to be believe their group is the only one doing anything?

If the people in this story stopped being selfish and arrogant ALL of the troubles that the good guys have had since book 1 would go away. Seriously, Rand learned not to trust Aes Sedai because Moiraine never told him a dang thing. She didn’t tell him what was going on because of 3000 years of Aes Sedai arrogance. If she had just talked to him back at the beginning, he would have trusted her, actually listened to her earlier and things would have been a lot different.

The fact that arrogance and selfishness are nearly tearing the good guys apart throughout the series is, I think, an important point. This is as much about how NOT to be a good guy (hello, Dark Rand) as it is how TO be a good guy.

I would counter your argument Leigh by saying that women tend to have similar closebonds with their friends and families far more often than men do.

The whole “Band of Brothers” thing often just boils down to the fact that after you’ve lived in close confines with a group of people eating bad food, working on little sleep, and being surrounded by people who hate/literally want to kill you will eventually wear down your armor enough that you can be more honest with the guy next to you going through the same shit.

Most guys will not willingly show effection or emotion under normal circumstances because society tells us not to is what I’m saying…

What isn’t shown in the movies or books as often is that its just as likely you will end up hating each other or getting on each others nerves will still retaining a “civil” if cold work relationship.

In other words chances are you have had a similar relationship by virtue of being a woman only without (necessarily) having to go through a lot of crap to get it.

Croaker41@18 – “The Killer Angels” is one of the best books ever written. Period. End of story. Nice to know I’m not the only one that thought of it while reading Leigh’s thoughts on the military.

@5: FWIW, I disagree with the statement that God does not intervene in the world. (Also coming from the Christian perspective) He created the world, is actively holding it together, and is at work in the world. I agree with the conclusion, though, that it would be presumptuous of a believer to take that to mean that he/she will never suffer disappointment, loss, grief, etc.

Regarding people who claim to speak for God, in the Bible, people were instructed to take what those people said and compare it to His known revelation (i.e., the scriptures) to see if what that person said agreed, and also to see if what they said would happen actually did happen. If what they were saying agreed with prior revelation and/or came to pass, then it was from God. If not, they were supposed to be toast!

In that sense, Galad appealed as he should have to the Children’s “scriptures” and “catechisms” to make his case (and should also be commended for making his arguments more to the other Lords Captain, with whom his arguments would actually carry weight, than to Asunawa, who had essentially co-opted the Children’s beliefs to benefit his own power and position).

“In fact, in the entire series, the only “direct” action we’ve seen the Creator take was when he showed up in TEOTW to tell Rand that he would take no part in the action!”

…Um, when the heck did this happen? I just recently re-read tEotW and I have zero recollection of this. Anyone want to help me out and pull the chapter reference for me?

I’ve really hated Fain through this series, he is a bug that needs to be stepped on. But with his powers growing I would like to see how his story plays out, one of the longest one in the series. I see him dueling it out with Shaidar Haran…

@hihosilver28

From Leigh’s re-read …

Jordan’s cosmology is an ineresting mish-mash of Manichaeism and Deism.

Also an interesting one.

Irish @@@@@ 14 – Trash Can Man!

@21 neverspeakawordagain

Thank you. I have been wanting to say something like that, but could never find the words. Glad I am not the only one thinking she is looking for any excuse to throw gender issues/politics/stereotypes into the mix.

@21. neverspeakawordagain I see it all the time, and it’s almost always men who are asking, “What’s with all the gender stuff?” Men often forget that as with so many other things in life, the default voice in literature is upper middle class white male. We are often oblivious to the gender stuff because it’s usually our stuff. Hello priviledge, my old friend.

Gender politics are a HUGE part of the whole WoT series. This is not something that Leigh is injecting into the story – it has been there from day one. Women’s Circle/Village Council, White Tower/Black Tower, Saidar/Saidin, etc?

Croaker41 @18 – I’d agree about Killer Angels, with one small caveat. She has to watch Gettysburg afterward. It is one of the few instances where there book and the film so perfectly complement each other. Instead of being able to say that the book was better or the movie was better, I found that each was perfect in its medium.

The only two books from college that I still read were both from ROTC – Killer Angels and Ender’s Game (I confess I reread the latter a lot more than the former).

@35 – At the same time, I’d argue that, as you mention, the default is white. As a minority, I see no need to worry over equal representation of other races in literature. People generally write what they know – and if you’re a middle class/upper middle class white guy, I expect you to approach that angle. If I’m looking for stories from other perspectives, I figure I’ll have better luck (and greater authenticity) if I find stories from authors that fit the design.

As an example, I’ve never been a woman, but based on my understanding of my wife and daughter, the depiction of Katniss Everdeen’s angst is pretty spot on. When I compare it to Collins’s depictions of the young men and what I felt, I feel like something is missing. At the same time, my wife is too often disappointed at how male authors approach agnst in young women when I find they are acceptable in portraying young men.

Discussing the role that women play in WoT versus the development of our society made sense earlier, but the horse has already been through the glue factory – at this point it feels like we are just looking for reasons to smack at bottles of Elmers.

Lisa Marie @12 – More specifically, the Battle of Agincourt took place on St. Crispin’s Day, October 25, 1415. Henry V, the young King of England, gained a significant victory over France. The speech Leigh quoted in the cut text and the commentary is from Shakespeare’s version of that day.

@30 – I actually have to say that I VEHEMENTLY disagree with her (Leigh’s) interpretation of that passage. That was NOT the Creator. That was the Dark One. He’s screaming out to the Dark One there, not the Creator. As we see later in the series, the reaction he has to the voice (making his skull vibrate) is the same we get when the Forsaken speak with the Dark One in SG. And as soon as that ends, he goes and fights with Ishy, who I think most would argue was the D.O.’s “Chosen One”, i.e. Nae’blis, at that point. This fact seems so GLARINGLY obvious that I am quite shocked anyone was confused into thinking this was an appearance by the Creator.

It baffles me, why do some still insist that the vocie Rand hears in TEOTW is the Creator’s?. Not only does this “Creator” name a Forsaken as “Chosen”, he is also responding to Rand’s actions, namely Rand’s wish to end every thing there.

He is basically telling Rand that now is not the time for every thing to end. Moreover, he will not participate only the chosen. Hence, it is clear that this “Creator” will be present when everything should end to oppose the dragon as Ishamal is doing in TEOTW. And please, do not mention the graphical disparity with the Dark One, as it was the first book and could have been retaind in later editions in order to spark this very debate…

I’ve always had a soft spot for Galad, despite his rigid sense of right & wrong (maybe because of it?), so this passage is covered in awesome.

Until Fain (or what used to be Fain) started playing with the trollocs, then…ick!

@36. RanchoUnicorno

That’s kind of like saying, “We already covered the topic of brotherhood with Mat and the Band of the Hand – talking about it with the borderlanders too is just redundent.” It’s a new book and a different author – it makes sense to keep touching base with one of the central themes of the series in each book of the series as they come up.

If it’s Leigh’s personal reflections on these themes that you’re not interested in then i don’t know what to tell you – it’s her show. I find her observations to be insightful and interesting and i welcome a different viewpoint that sheds light on things from a new angle, but i guess you could just skim for the parts you can relate to if you want.

@39 and 40

I would counter your arguments with the very evidence you presented.

The DO uses the term Nea’blis and “Chosen” The Creator uses “Chosen one” a slight difference granted–but let us also remember that the DO and Creator are very close in power and substance according to Jordan himself. It stands to reason that their minds would be twisted reflections of one another.

Much of the cosmology of the WoT ‘verse was taken from the ancient Zoroastrian religion which had two equally powerful gods at eternal war (one good the other evil and imprisoned).

It therefore makes sense that the Creator would have his own “Chosen one” to act as his champion to oppose the shadow. The people of the world are his “hordes” because they choose to protect what they have through sacrifice rather than trying to destroy in selfish ambition (different but the same).

Also–the DO very explicity takes direct influence via screwing with the weather and the fabric of reality. He may be the “Father of lies” but he makes no bones about that.

@28 — After Rand kills Aginor, while he is running through, um, like clouds or some stuff, up a staircase to fight Ishamael, with the battle at Tarwin’s Gap raging beneath him. There’s an ALL CAPS interjection which is (presumably) the Creator saying he will take no part.

Interesting insights@39 & 40 Not the Creator. hummmm, have to think about that…… I really understood where Galad was going with this line of questioning. Finally he was making true sense.

The Tower scenes still make me tear up no matter how many times I have read it! Fain….FAUGH, I get shivers just reading about him, undead Trollocs???….

Thank you Leigh, for the post, good night Gracie!

@42 You’re right. I should have thought of it from that point. I guess my point was that this discussion began on the brotherhood topic and ended up back in the land realworld gender politics. I would be just as frustrated if Leigh was using each mention of racial/ethnic/naitonal relations to go over the topic of racial stereotypes and representation in fantasy and in realworld situations. In both cases, my issue wouldn’t be addressing the topic at hand, but reverting back to an issue that isn’t a point of focus here.

In the end, you’re (again) right, that it’s Leigh’s show. Nevertheless, I still feel compelled to point out areas that she seems to struggle with. Her posts are fun to read and she does an excellent job of putting pieces together that I had forgotten about and bringing the stories back to life – I just want her to go from 10 to 11.

Anyway, back to the post, which I neglected to address earlier.

This was the moment that I began to actually like Galad and the COL. Before, I appreciated his strong sense of right and wrong, no matter the cost, but had yet to see it really cost him. Now, much like Ned Stark, his honor cost him. In both cases, they were willing to give their lives and sacrifice their honor in the face of the world, if it meant holding to a greater honor and protecting their families (inasfar as Galad’s family is the COL). That the COL found their way under Galad suggested to me an organization with noble intent, but corrupted by the failures of the men who led them.

The borderlanders….again, faithful in their duty to protect their families (and in this case, the family of all mankind). Shivers, every single time.

Neverspeakawordagain @21 and others: I think Leigh would be remiss in not commenting on gender politics- pretending that it’s not an issue in the text, or even just an issue Jordan didn’t intend to approach, doesn’t do good service to anyone commenting on the text. Gender politics and gender issues are something most every major character and storyline grapples with at some point or other.

Of course, if you’re just reading for fun, looking too closely at the text and themes might be distracting- perhaps particularly since the issue of gender politics is still sufficiently present in modern western civilization that looking squarely at it can be uncomfortable. It might even permanently affect how you view some scenes (I, for one, thought The Tylin Thing was pretty funny on my first uncritical read-through). But we have no compunction here about dissecting and analyzing every other aspect and theme of the text; why should this be special?

You could argue that “sure, gender politics have to be addressed, but Leigh brings them up more often than necessary”. For one thing, it’s her re-read, and somewhat subjective by design. I’d further suggest that if the gender issues in a scene are relevant enough to bother her, that in itself makes it relevant enough to comment on. Perhaps the question is “what about this bothers some readers but not others”, but it’s not a non-issue. [I do note that Leigh’s subjective commentary on other major issues (like, say, the personal-faith-and-morality questions in this very post) may to draw dissent, but rarely the “why are we talking about this at all” response.]

Finally, I’d suggest that if all the other commentaries you’ve read have chosen to ignore gender politics, that’s more reason, not less, to address them here.

Leigh,

Life is a bitch in many ways. Men and women are different. I sat by my wife’s side through three caesarian delivieries. I literally wore blisters on both my hands rubbing her back through 18 hours of back labor with our first child, but nothing could relieve her of the task of delivery. In the end she had to go through it and I was in reality nothing more than an outside observer. Never in the 32 years since that day has she ever said it wasn’t “fair” that I didn’t have to go through that or that she would have traded places with me. Women have a lock on the child bearing/nurturing/ breast feeding part of being a parent – that is just the way it is and is not subject to our thinkso or wants and wishes. I started this series with my son in 1996 when my son was a not so literate sophomore in high school as an attempt to get him interested things other than baseball. He was the cause of the blisters mentioned earlier. This has been a long journey sitting along side the books as a casual observer, but the delivery is at last at hand. As for Killer Angels, highly recommended as we are all fighting for our “rats”.

Croaker41 @@@@@18:

Thank you for the rec, I will check that out!

neverspeakawordagain @@@@@ 21 (and others):

I’m sorry you feel that way, but I’m not sure why, when it has been unambigously clear throughout this Re-read that I am approaching the commentary to WOT from a feminist perspective, that you would continue to be either surprised or baffled by it at this late date. If it is not to your taste, you are of course completely welcome to stop reading it.

And for what it’s worth, though you may not choose to believe this, 99% of my commentary is not actually planned with any specific agenda in mind at all, feminist or otherwise. The only actual rock-solid agenda I have in doing this is to be honest in my responses to the text.

I talked about how the nameday ceremony made me feel excluded because that’s how it made me feel. You are free to disagree with how it made me feel, of course, but I’m afraid you don’t get to tell me I have no right to feel it. Or to talk about it.

And I would apologize for (apparently) distracting you with my “femaleness” as a writer, except for how you really just made the point of why the feminist perspective is so badly needed in sf literature for me. So instead I will simply thank you for the unintended compliment.

Sooner_fan @@@@@ 22:

Your point is taken. However, I am under the impression that women (in the U.S. military) are still not officially allowed in combat, and that the recent instances counter to that have arisen more or less because the situation is simply too chaotic to prevent it. If I’m wrong in that please do let me know.

Neverspeakawordagain, Dolphineus:

You know by now how Leigh reads and interprets the Wheel of Time books. You also have to be aware that she’s not the only critic who sees gender issues in the series. That is: you know that Leigh’s readings are legitimate, and that they fall well within the canon of Robert Jordan criticism. You just don’t like them personally.

Life can be so hard.

If you don’t like the re-reads, don’t read them. Whatever you do, stop ragging on Leigh.

I swear, Leigh and I did not rehearse that.

Awww Leigh, I was looking forward to your commentary on Loial’s pre-prologue…

IIRC, didn’t someone ask about the “Creator Speaks” at a book signing or similar event, and Brandon said something to the effect of we (the readership) might be making some assumptions about what happened in that scene, but it was ultimately a RAFO? I might have dreamed the whole thing up, but sound familiar to anyone else?

I’m of the opinion that Galad’s response to Asunawa is just that, a response. He’s not himself operating under the belief that moral rectitude is an adequate substitute for training, just kicking the crap out of Asunawa’s claim that he won through Infernal Support. Galad seems more the “may I live up to the standards God expects of me” type.

Really, that’s what makes him one of the good guys. The villains, on Team Shadow and elsewhere, are the ones who think they deserve that the universe live up to their sense of entitlement.

—

Braid_Tug @11: In fairness to Galad, Rand, Egwene, and Lan haven’t exactly been playing icons of hope and unity on-screen long enough for Galad to have heard about it. He’s still getting the Dark Rand and Rebel Leader part of the news cycle, if anything.

—

Galad’s story mirrors Egwene’s, but I think that’s part of a larger pattern- from the very beginning of the series, the whitecloaks, as an organization, have always had far more in common with the tower than with anyone else. And vice versa, even with the wise ones and the windfinders and what-all else in the mix. The whitecloaks are basically the male version of the tower (with military prowess substituted for magical), and they need the same sort of back-to-core-values prod in the buttock.

—

Gadget @17: I think the evidence is in favor of Galad’s introspectiveness being well above average for WoT (not a high bar to clear, but still). He’s not on screen much before now, but he does seem to put thought into questions like his decision to join the whitecloaks. Or how he should react to Elayne and Nyn when they show up as fugitives in Amadicia, his indecision over which gives them time to disappear into the circus.

@33 thepupexpert – Thanks, good ol’ Trash Can Man…

Fain- I still think he’s going to take down, or allow one of our hero’s to take down a major Forsaken/ Shaidar Haran – somethin…

just to smack some bottles of elmer’s around…

smacking heads! a.okay

smacking bottoms! noooo :waggles finger like Alec Baldwin in the Capital One commercial:

o yah… M-O-O-N, that spells Fain.

tnh @@@@@ 51:

We really didn’t. Heh.

AhoyMatey @@@@@ 52:

D’oh!

I totally meant to put that in, I swear. Okay, next time for sure.

@43 – I have to disagree, and I don’t think this is one that will really ever be solved textually. Most likely it would need a direct revelation from Team Jordan to answer it definitively. However, I point back to the passage: Who is Rand calling out there? Ba’alzamon. He’s not calling out to the Creator. He says, Light blind you, but that is a very common phrase in this world. And the full sentence is “The Light blind you, Ba’alzamon!” That is who he is screaming out to.

You use to argument of Chosen vs. Chosen One, but I think that is really flimsy. There are way too many instances where changes on the part of authors, or typos, or them just forgetting adding a single word in a single way have happened to lend that much credibility as an argument here.

While yes, it’s true that the D.O. has been willing to take a more direct hand wherever he could, let’s also remember that at this point in the series, most all of the seals were still intact. His prison was a lot stronger than it was say, when the Bowl of the Winds was used. The only hand he seemed to play even then was manipulating the weather, and that apparently took a lot out of him. To the point that the Forsaken (I don’t recall which one) mention how angry he must be that the weather has been set to rights. In the past two books, we are seeing his hand more directly, but even then, it is still fairly indirect. It appears to be more the influence of his evil on the world, possibly combined with Rand’s liberal use of balefire eroding the fabric of the Pattern, which is causing a lot of what we’re seeing. I’m honestly not sure how much more of a direct hand the D.O. can take than what we have seen. We’ll find out at Tarmon Gaidon obviously, but it comes back to the idea of whether or not he can actually physically strike out, which I’m not sure that he can. He uses proxies. He did so even during the War of Power when there was no seal on his prison, just the bore. It therefore makes perfect sense, that at a point in time when he wasn’t ready for the Last Battle, he would say that only his Chosen One would fight, not him.

There are two major problems I have so far, in -this- part of the prologue:

Fain:

The shadow/dark/naughties are supposed to be hunting him down and killing him. There should be no way he’s still alive at this point in the game. Hesitation and “err… maybe we should… uh… give him the business?” shouldn’t be a part of the Dark Forces of Evil’s repertoire. It diminishes not only your every-day ornidary shade, but where the hell is Shaidar Haran? Fain should be dead dead dead dead. The Dark One should have put one of the Chosen on this a long time ago. Go the freak away, dark-grey-jerk.

The “Towers of Midnight” themselves. Which I attribute to the watch stations along the blight, rather than those stupid shonchon things we’re supposed to believe, or whatever.

That there isn’t a way for the towers to know exactly what is going on at exactly the moment they’re happening deminishes their use. There should be a signal that goes out the minute The Evil Forces of Evil even show themselves. “Hey, bad guys are attacking us, if we don’t let you know the outcome/status in one minute, get ready.

Come on, man.’

Oh, and as far as “no girls allowed,” just let me tell you a little secret about this guy who tried to join the Marines in 1990…

He had fallen arches, and bad hearing.

tnh@51

Superb! …and very well said in the first place. This is Leigh’s re-read, and it’s all about her impressions, not anyone else’s. If feminist issues are what comes to mind when she reads the chapter, that’s what she’ll write about, just as she has for the last twelve books worth of entertaining and informative commentary.

There is nothing in the text suggesting that this is a sentiment of the dark one. But it is a repeated theme of the story to say that the Creator takes no hand.

“Chosen one” is so very different from “the Chosen” it hardly needs to be argued. Whomever is delivering this line, they have tapped a champion to complete their work. To think that this is the dark one makes me ponder Shaidar Haran. Moridin, named nae’blis, still is aware that he isn’t going to be the one completing the task, but is merely a role-player waiting for the Wheel to stop, so that he can rest. Meanwhile, The Hand of the Dark, Superfade, is giving orders, making plans, and punishing poor performance among the dark one’s chosen. If anyone is the Shadow’s champion, it is he.

The dark one is not known for permissiveness. Conditional behaviors are not very acceptable to him. Sounds like a more benevolent party to me.

Gah, double post of some sort.

JackJack, I’m not seeing a double post from you, and you’re not the only reader today who’s reported a double post that wasn’t there. We may have a new site bug.

tnh:

I was trying to amend my post, but it reposted the whole thing without what I had added. I edited, then erased everything instead of rewriting what I thought. In any case, I think it has more to do with my noscript monster than anything I or the site did.

On the subject of religion, what Free said. Faith does not work that way.

Heath will stand. Beautiful and simple.

Rites of passage. Yes, it is good being a guy sometimes, but remember, those bonds are forged by extreme conditions, I would not be too wistful to be placed in such circumstances, they are not as glamorous as one would think.

And my bond with my fellow soldiers pales in comparison to the bond my wife has with my daughter. There is depth and there is depth.

Fain. I told you so. The guy needs a serious time out. In the corner. On the “no-no chair”.

Galad. Well, he’s got Berelain to make it all better afterwards. I do like his sentiment about the role the Children have to play at the LB. At least, he is one of the few that have thought it out to the point where Aes Sedai enter the equation, that is more than some.

…. Maybe some of Leigh’s disappointment stems from the way that Galad was brought down and disciplined. He was beaten and knocked out, not spanked:P

Woof™.

woofie:

After rereading the reread (WAT? I KNOW) it occurs to me that Nynaeve would be completely content to admister the spankings to Galad that he deserves.

As of TFOH, at least.

Thanks, Leigh.

I’ve always considered myself a feminist, and yet there are times when gender issues just don’t cross my mind. I appreciate it when you bring them up, point them out, and raise my awareness! I think when reading, I forget what sex I am, and identify with the character. It’s kind of fun to be a guy once in awhile…even if it’s only on the page.

Some good points were made above about the “brotherhood” of men. It often takes extreme circumstances to bring out emotions in men….to create that comraderie. I don’t envy them. Women seem to be a bit better about sharing the emotional stuff, instinctually. Vive la difference, eh?

{If you want a read where the men and women in the military are completely and utterly equal, try Malazan. I love Erikson for that….and many other things ;-) His main characters are the common soldiers……and they are awesome. They all seem to have nicknames, and you really can’t tell if they’re men or women, and there are plenty of women combat soldiers.}

I do wish we’d get a bit more detail on Fains growing abilities and insanity, as he’s still in this game, and presumably will play some part in the last book.

I think Galad used the proper approach with the hateful Asunawa. Beat him at his own game! He really does shine the light, so to speak, on Asunawas sickness, which plays out nicely a bit later. Galads thoughts show that he is a pragmatist too. He knows he has to ally with the Aes Sedai, and the Dragon to fight the last battle and that is the right of it!

Forgot to add that the ending, was extremetly touching.

Oh, gawd. My brain just created Birgitte/Galad fic. Kill me now. Or take away my booze.

BTW, as a follow up to the Fallen Angels theme I just spent Thurs night – Sunday afternoon at Gettysburg. My mom and I did a three day photoshoot at the battlefield. We shot Day One on Friday, an exhausting Day Two on Saturday (Culps/Cemetary Hills however are much easier done first rather than last) and then we parked at the Virginia Monument and walked the entire field of Pickett’s Charge to the High Water Mark and back to close the trip. If you are in the area I highly recommend the B&B’s of New Oxford rather than the hotels of Gettysburg itself. Great long weekend with perfect weather I must say.

BawambioftheChamberlains20thMaineAiel

Oh, dear. I usually remember well the content of books I like / am impressed with, yet when it comes to Killer Angels … which I recommended to everyone who would listen after I read it years ago … had completely slipped my mind until Coaker41 mentioned it.

I too thought that it must be the Creator who spoke in TEotW, but there are certainly compelling arguments both ways.

Thank you, Lisamarie @12, for asking about October 25. I suppose if I’d Googled it, I would have found an answer, but meanwhile, you asked and Wet answered!

@Irish & Cor – I just went back and watched that whole series on Netflix not too long ago, it’s all there. The actor who played Trash Can Man in the series is too tall and not nearly as ugly as I envision Fain to be. That actor had a running part in Next Generation but forget his name…

On topic… I think this is why I love this reread so much, it does make me squirm a little bit sometimes.

neverspeakawordagain@44

Rand did not kill Aginor. Aginor toasted himself by drawing too much of the OP from the Eye.

——

Re Leigh’s commentary: Leigh’s commentary may occasionally cause some of us to slap our heads, some of us to clap our hands, etc. Have you noticed one thing though?

She’s never dull.

That would be a cause for complaint – but she bats 1.000 in the most important thing: Keeping it interesting! Oh sure, I’ve rolled my eyes at times (as have many of you when reading my comments, I’m sure.) But I’ve yet to “skip over” anything she’s written. I would not make the same claim about some of the comments.

I’d feel worse for women in WoT not being allowed into the “brotherhood” of men at arms, if they didn’t have a series of GIANORMOUS sisterhoods that men aren’t allowed to belong in, which allow them the opportunity to fight against shadowspawn and the Dark One. It’s not like men are allowed into the Aes Sedai, Kin, Wise Ones, Windfinders, etc. and at least with the Aes Sedai and Wise Ones both participate in war, the Aes Sedai even have an entire ajah that’s soul purpose is to fight the Dark One and call themselves “The battle Ajah.”

Now that’s not to say that in a perfect world men and women wouldn’t be working together to fight shadowspawn and the Dark One, but since the purpose of the series and the entire story is about bringing them both together to fight against a common enemy, I feel like Jordan is bringing this up and answering it.

Thanks again, Leigh!

Reading Leigh’s summary of the end got me a little choked up, myself. If that last bit doesn’t make the reader feel even a little emotional, then I really do feel sorry for them. I agree; the reread may have made it more emotional, although for different reasons. As a rereader, you know the fate of a number of faceless Borderlanders. Here, Team Jordan has put face and names to those lost. Good stuff!

I forgot how much I like the prologue of ToM. When I grab ToM to get my WoT fix and read a few chapters here or there I usually go to Rand vs Egwene; or Rand reuniting with Tam; or Rand vs 1000s of Trollocs in Maradon; or Perrin vs Slayer/Egwene vs Mesaana; or Perrin forging Mjolnir (spell it how you like); or Mat’s letter; or Mat in the Tower of Ghenji; etc…

It was easy to forget that this prologue is incredibly important (and a great read). However, I think that one aspect of the prologue stands above the rest in its importance. Yes (as the last post shows us), we discover the fate of Graendal (and Arangar and Delana) after Natrin’s Barrow; and we get to see Lan begin to walk down his path; but the more important part of the prologue is the evolution of Galad.

ToM is a novel where a number of our characters accept their destiny/fate and/or evolving into the type of leader the Pattern needs them to be. The obvious candidates are Perrin, Rand and Lan. But another important arc of evolution is Galad and the Whitecloaks.

It’s easy for the reader to wrap in the Whitecloaks with Perrin’s army (partially, because that’s where they end up), but the development of Galad and the Children of the Light into a force that will work with the Dragon Reborn and his allies (including Aes Sedai, Ashaman, Wise Ones, Windfinders and other channelers) is an incredible step forward from where they started off in TEotW. And the development is all due to Galad’s change in perspective.

As for the rest:

Fain: Sooo creepy. Sooo powerful. Sooo twisted. So good. I enjoy that, just like with Lan, ToM begins and ends with a look at the impact of Fain.

The Kandori: I love this section. I appreciate how Team Jordan was able to make us feel for these characters that we had never met. I… can’t find the words to describe how this makes me feel, from the perspective of Malenarin, Keemlin and the surrounding men.

Their choices (Malenarin’s desire to see his son safe; Keemlin’s compassion in sending Tian so that Tian’s mother wouldn’t lose another son; and Malenarin’s realization that his son was indeed a man, and should be elevated as such) and their willingness to stand to the last breath. It is so moving. I may have to go home and reread this section tonight.

Distinctions in gender impacting the options of individuals in regards to the US military: I do agree that it’s a thing; not sure if I want to discuss it here. I’ll see how the comments flow… I did appreciate Leigh’s observation of the dichotomy of her feelings regarding the “brotherhood” and “men” passages.

Yeah, Leigh’s comments about sexism and religion weren’t controversial at all… :-)

As for the comments:

BenPatient@@.-@ – I like the example that you gave, in regards to feeling left out. It’s possible for men to relate in that regard. The obvious counter is that one type of discrimination is biological, while the other type is based on social construct and sexism. But I appreciate the comparison. There are some things that men will never be able to feel/experience, regardless of what country they are born in. MAT@7 and others mention this too.

Wishflower@16 – re: tears-worthy scenes – I have to agree that the only scenes that really seem to “get” me in good movies, television and/or books are related to honor and self sacrifice for a worthy or greater cause. No matter where I am, the room tends to get real dusty all of a sudden, and the dust always finds its way into my eyes…

Sps49@20 – Thanks for the updates in the slowly improving gender equity of our armed forces. Last I heard (probably from some tv show awhile ago) women weren’t allowed to serve on submarines; I’m glad to hear that has changed.

MatthewB@35 – I do respect your point that what is considered the default perspective in most aspects of our society is usually slanted as the middle class white male perspective. Tor.com has actually had a few interesting posts that have discussed this in more detail: one about the presentation of women in marketing movies/tv/books, and the other about increasing diversity in the world of RPGs. I’d encourage others to check them out.

Having said that, I think that it is fair criticism of Leigh to suggest that she often brings gender concerns into her discussion. However, this is her blog/post and that is one of the main responses that WoT brings out of her, so it would be “untrue” of her to not discuss this topic when the text leads her to feel that way. Others may feel different about what the text means; that’s their right. As long as we discuss it with respect for each other’s perspectives, I feel that these discussions add to the post.

Jhirrad@39 and Bilar@@.-@0 – re: “the voice” – Ha! I was waiting to see if anyone challenged whether that was the voice of the Creator or not. I’ll just say that at this point the reader doesn’t actually know who the voice was.

Looking Glass@@.-@7 – re: Leigh’s focus on gender politics – I see you got there first. Good points. I also laughed initially when I read about Tylin’s pursuit of Mat. Until she threatened him with a knife and cut his clothes off. Then I thought about what was really going on…

leighdb@@.-@9 – re: agendas – Oh, I don’t know. I think you have a very strong pro-headdesking and anti-spanking agenda :-)

tnh@51 and leighdb@58 – I don’t know; that seemed pretty well coordinated. Someone may have to call “shenanigans” on you guys for that one…

CorDarei@56 – Well see, if they’re hardheaded, you should be smacking them in the head.

Tektonica@68 – I echo your sentiments regarding Malazan. The characters are awesome, and sometimes you forget which gender they are. Or, you make the wrong assumption regarding gender before the author drops matter-o-factly what gender they are. Erikson does a masterful job. A continuous “Thank you” to you and the others on this reread for talking me into reading Malazan.

Jackjack@69 – Wouldn’t Galad be too pretty for Birgitte? But for us to take away your booze? Never that! Take another swig, I say!

forkroot@73 – Yes, Leigh is definitely not dull. I also appreciate the fact that she introduced “headdesk” into our lexicon…

Sorry if I missed this in the comments, but what were the mechanics again why the Trollocs rose again after being touched by A Mighty Wind, but the Myrddraal does not?

The Fade’s touch is death to its kind (other Fades, yes?) and *that* causes it to not rise?

How does that work? I am flummoxed.

forkroot @@@@@ 73: